A beautiful whitetail buck taken with a flintlock. Image courtesy Pennsylvania Game Commission.

In the United States, muzzle-loaders constitute a significant percentage of the rifles carried afield every hunting season. Impetus for a resurgence of general interest in muzzle-loading rifles resulted from the Centennial Celebration of the American Civil War; enterprising individuals (notably Turner Kirkland of Dixie Gun Works, and Val Forgett of Navy Arms) contracted with arms manufacturers in Europe to produce more or less faithful replicas of mid-19th Century guns. These were sold mainly to re-enactors and collectors who couldn’t afford (or didn’t want to shoot) original guns.

Many replica guns were used for hunting but the large market for dedicated hunting muzzle loaders—as distinct from rifles used by re-enactors or history buffs (known as “buckskinners”)—and fierce competition among gun companies inevitably led to technical advances to increase power, accuracy, and convenience. Those simplified the process of taking game with a “primitive weapon,” and met the demand of hunters who just wanted a longer season and didn’t give a hoot about historical authenticity. While the muzzle-loading hunter of 30-40 years ago used a sidelock rifle of traditional design with open sights, since the mid-1980’s sidelock guns have been more or less replaced by “modern” designs, typically break-open in-lines with telescopic sights, using a shotgun primer for ignition.

The most significant factor that made muzzle loaders appealing to American hunters was the remarkable increase in populations of white-tailed deer since the mid-1970’s. To facilitate reduction of burgeoning deer numbers (which had actually risen to nuisance levels in some places) most states created so-called “primitive weapon” rules and seasons to give users of muzzle-loading guns additional time in the field and/or more liberal bag limits. In-lines came to dominate the hunting market and declining sales of sidelock rifles caused some manufacturers to drop them from their product lines.

Nevertheless there are always individuals for whom the guns of the past exercise a real fascination and who accept the challenge of using “old time” equipment as effectively as their ancestors did: I’m one of them. I began hunting with muzzle loaders in the early 1990’s. After some years I became interested in doing it “the hard way,” the way the frontiersmen who settled my part of the USA did it 250 years ago. That meant using a flintlock rifle.

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers Through the Cumberland Gap

An 1851 painting by George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879). Bingham was a major American artist whose work portrayed frontier life. This painting of the renowned American explorer and pioneer, Daniel Boone (1734-1820) shows the importance of arms in pioneer society. Every man in the party is armed with a flintlock rifle to hunt and defend himself and his family against danger.

Interestingly enough the final stages in the perfection of flintlock technology coincided with two very significant historical events: the settlement of both sub-Saharan Africa and North America by Europeans. Prior to 1807, the flintlock had been the dominant form of firearms ignition for at least 200 years: by 1600 flintlocks in much the same form as we know them today had supplanted the matchlock and wheel-lock for most uses. The early 17th Century saw establishment of the first English settlements in North America and the initial arrival of settlers at the Cape of Good Hope. In the early 19th Century, Boer voortrekkers armed with flintlock rifles and fowling pieces moved northward to escape British domination. With their flintlock rifles they hunted for food and conquered the indigenous peoples of the interior.

Interestingly enough the final stages in the perfection of flintlock technology coincided with two very significant historical events: the settlement of both sub-Saharan Africa and North America by Europeans. Prior to 1807, the flintlock had been the dominant form of firearms ignition for at least 200 years: by 1600 flintlocks in much the same form as we know them today had supplanted the matchlock and wheel-lock for most uses. The early 17th Century saw establishment of the first English settlements in North America and the initial arrival of settlers at the Cape of Good Hope. In the early 19th Century, Boer voortrekkers armed with flintlock rifles and fowling pieces moved northward to escape British domination. With their flintlock rifles they hunted for food and conquered the indigenous peoples of the interior.

Flintlocks were eminently suited to the needs of pioneers. Compared to the clumsy, dangerous and awkward matchlock and the complicated, expensive, delicate wheel-lock, the flintlock offered the virtues of mechanical simplicity, ruggedness, low cost, and high reliability. The internal mechanism was simple enough to be repaired by a country blacksmith; even more importantly, flintlocks weren’t dependent on an industrially manufactured article (i.e., percussion caps) that had to be transported over the sea or on primitive roads at great hazard. All that was needed to keep one working was a local source of flint and gunpowder (which could actually be homemade). This convergence of the economic needs of expanding frontier societies and the perfection of the lock design kept flintlocks in widespread use long after the development of the percussion cap. Even now flintlock rifles in traditional styles are still manufactured. “Production” guns by reputable makers are sold at affordable prices, and many custom makers turn out hand-made rifles of exquisite workmanship and quality (with prices to match). Thanks to modern materials and manufacturing methods the new-made guns are stronger, more reliable, and usually more accurate than even the best of the original ones.

But to use a flintlock rifle effectively requires a different mindset than a conventional rifle; when you’re using 18th Century technology you must think and act like an 18th Century man! It’s the purpose of this essay to discuss in very general terms things one needs to think about and to deal with when hunting with a flintlock. Some of these issues are technical, others are what might be called “behavioral,” but are all derived from the essential nature of the flintlock’s design and operation.

HOW THEY WORK

It has been known for millennia that a piece of steel struck by a flint will generate sparks. Sparks are actually minute red-hot fragments of steel chipped off by the hard rock and knocked loose. If they fall onto a suitable material the sparks will ignite it. Flint-and-steel fire making was well established long before gunpowder was discovered in the mid-13th Century. Black gunpowder is extremely sensitive to a spark, igniting virtually instantaneously when one touches it. Once gunpowder had been discovered its adaptation to weapons was inevitable and the application of the principle of flint-and-steel to firearms ignition was also bound to happen.

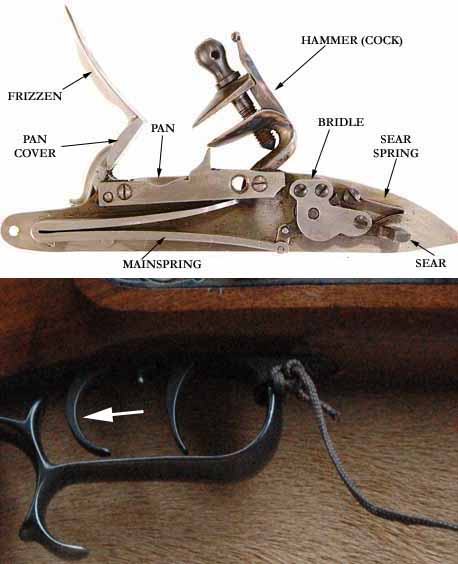

A flint lock has several basic parts. The “cock” (or hammer) holds a sharp piece of flint in a pair of adjustable jaws and the “frizzen” is a curved piece of steel against which the flint is struck at high speed. As the cock flies forward it kicks the frizzen back, exposing a shallow pan full of powder. The bits of metal the flint knocks loose are red hot because the energy stored in the lock's mainspring is translated into heat when the forward movement of the cock is suddenly stopped by the frizzen face: the sparks ignite the pan powder. The more sparks the better: the strength and abundance of the sparks thrown by the lock are the most important factors in determining the reliability and proper functioning of the lock.

At the breech end of the barrel a small flash hole communicates between the main charge and the blazing priming pan powder. Fire from the pan charge passes through the flash hole and sets the main charge off. Assuming a properly sparking lock, the right amount of priming powder, and a clear path to the main charge, the gun will fire.

Watch this happen here! In this short video clip you can easily detect the split-second interval between the ignition of the priming charge and the main charge. The fairly long "lock time" on the flintlock rifle (compared to percussion guns or those using fixed ammunition) is something a hunter has to be aware of: it's an inevitable consequence of the lock's mechanism.

TECHNICAL AND MECHANICAL ISSUES WITH FLINTLOCK IGNITION

As simple as all this may seem there are some inherent pitfalls. Mechanical and technical matters can be dealt with if the shooter does his part. Assuming the manufacturer has produced a lock with good materials and the correct relationship of its parts, a hunter has to learn what to do to minimize the chances of a misfire, coming to understand the idiosyncrasies of his own rifle: what it “likes” and “doesn’t like,” and how to make it fire as reliably as he can. That said, he also has to be philosophical about misfires, because sooner or later he’s going to experience one. It goes with the territory.

Keep The Lock Clean

One basic thing to keep in mind is that the lock works best when it’s clean and dry, and when no oil or grease has been allowed to contaminate anything. A flintlock is by its nature essentially open to the weather. Flintlocks are notoriously affected by wet weather, and it’s a frustrating activity to use one in a rainstorm. If the priming powder becomes damp and doesn’t ignite the gun won’t go off. If the priming charge detonates weakly and doesn’t set off the main charge a puff of smoke comes from the pan but nothing else happens. (It’s from this fairly common occurrence that we get the phrase “a flash in the pan,” meaning something that promises much but fails to deliver results!) While it’s possible to protect the priming charge against the environment to some extent, all too often a hangfire or misfire ensues under such conditions.

Flash Channel Blockage

A blocked flash channel is another source of a misfire that’s quite separate from a weak or too-small priming charge. It’s important to be sure that fouling residue has been cleaned from the pan and the flash channel. If the gun has been fired recently priming powder fouling may clog the tiny flash hole, preventing detonation of the main charge on the next shot. A good practice is to clear the flash hole every time the gun is prepped for use, using a wire or fine pick to make sure it’s free of any obstruction.

The Flint

The flint may be a source of trouble. A dull flint, or one that’s not properly adjusted in relation to the frizzen can cause a weak spark. Flints work best when they’re sharp, and when they impact a clean, smooth, polished frizzen face. A poorly sparking lock might also be the result of a weak mainspring. But whatever the cause, a poor spark usually produces a misfire or a hangfire.

Flints aren’t immortal. Sooner or later the edge of the flint that strikes the frizzen will become dulled from impact, so it has to be dressed and squared up to the frizzen face. Luckily it’s possible to buy good quality flints from commercial sources so it isn’t necessary to knap your own from a larger chunk of rock. Dressing and squaring the edge of a flint is done with a small non-sparking brass hammer; there’s a bit of a learning curve associated with this activity but it’s not difficult to do.

Lock Adjustment

The relationship of the flint’s leading edge and the frizzen is important. You want as much of the flint’s edge to strike the frizzen as possible, as hard as possible, and as squarely as possible. The jaws on the cock have to grasp the flint very firmly so it won’t move on impact: hence they’re padded with a bit of leather (or even sheet lead) so that their grip is strong and the flint doesn’t slip. The top jaw has a screw in it to tighten the clamping force; a screwdriver is used to open the jaw to replace the flint or to re-set it as its front edge gets worn.

The proper alignment is made with the hammer at half-cock: the leading edge of the flint should be positioned just barely clear of the frizzen face, and parallel to it. That way when the hammer flies forward and the flint strikes the frizzen it takes a good “bite” and creates showers of sparks. Every few shots the shooter will need to check the alignment and the flint/frizzen clearance to make sure it’s correct, adjusting as necessary. Obviously at some point the front edge will be so worn away that the flint is no longer usable.

The Frizzen

The frizzen has to be kept clean and smooth-faced. This last is very important: the frizzen is ultimately the source of the spark, and if it’s dirty, pitted with corrosion, or contaminated sparking will be weak. One of the things a careful flintlock shooter comes to do more or less by reflex is to burnish the frizzen face after each shot using a bit of fine sandpaper.

POWDER

Hunters using percussion-ignition rifles—especially in-lines—have a lot of options in propellants, including several “replica” powders that are much less sensitive to sparks than “real” black powder. Replica powders burn very rapidly once they get started but aren’t liable to ignite except under specific conditions. This reluctance to ignite makes them far safer in shipping and storage than black powder, but it also means they’re not well suited to use in flintlocks. The flintlock hunter has one option: “real” black powder. Nothing else works as well.

Several commercially-available brands of black powder. The overwhelming dominance of "in-line" rifles using "replica" powders in the hunting market make it difficult to find real black powder in some localities, but mail-order houses catering to black powder shooters can provide these and other brands. It is legal to purchase black powder without any sort of permit in most states; Federal regulations permit quantities up to 50 pounds to be held without special storage requirements. GOEX brand is made in the US and can be purchased over the counter in some places, especially where hunting regulations require the use of flintlock rifles in the special season.

Black powder is still commercially made. In fact it's one of the few industrially-manufactured commodities that has been in continuous production for 800 years or more in substantially the same form. It’s not really a “powder,” but rather a mechanical mixture of its components formed into granules of different sizes, from quite large to exceedingly fine.

The grain size determines the burn rate of the charge: the finer it is the faster the charge will burn and the higher the breech pressure it will develop. The most common designation for grain size uses the letter “F” to denote fineness. “1F” powder is very coarse and unsuited to sporting guns. The “2F” and “3F” sizes are most commonly used as the main charge propellant; the very fine “4F” is used only as powder for the priming pan, never as a main charge.

Black powder has to be kept away from sparks, obviously. In the field, the hunter must carry his powder in a non-sparking container. The traditional powder container is made from a cow’s horn, but more modern flasks with dispensing spouts are more convenient. A flask should be made of brass, not steel.

THE FLINT

The flint is the key to the system. A form of crystalline rock found in abundance in some locations, especially in sedimentary formations, flint can be worked into various forms of edged tools and was one of the first materials used by primitive Man to modify his environment. Flint has been used for many millennia to make knives, arrowheads, and to start fires. It’s well beyond the scope of this essay to discuss the making of gun flints, but it’s not necessary for the individual shooter to do so: commercial sources exist for both natural flints and manufactured ones. In general natural English or French flints are regarded as the best quality, but which type works best in a given rifle is a matter of experience. The image above and at left shows a couple of hand-knapped flints, and some commercial flints made from other materials. In my experience and in my rifle the natural flints work best,

The flint is the key to the system. A form of crystalline rock found in abundance in some locations, especially in sedimentary formations, flint can be worked into various forms of edged tools and was one of the first materials used by primitive Man to modify his environment. Flint has been used for many millennia to make knives, arrowheads, and to start fires. It’s well beyond the scope of this essay to discuss the making of gun flints, but it’s not necessary for the individual shooter to do so: commercial sources exist for both natural flints and manufactured ones. In general natural English or French flints are regarded as the best quality, but which type works best in a given rifle is a matter of experience. The image above and at left shows a couple of hand-knapped flints, and some commercial flints made from other materials. In my experience and in my rifle the natural flints work best, but each lock is different and your mileage may vary in this respect. Below at right are some chunks of natural flint as found: they have to be chipped into the proper shape and size to be used in a lock.

but each lock is different and your mileage may vary in this respect. Below at right are some chunks of natural flint as found: they have to be chipped into the proper shape and size to be used in a lock.

Gunflints come in different sizes. Gun manufacturers will provide guidance on what size is best to use in a specific lock, a matter of some importance. If the flint is too large it may be so long it can’t be set at the proper distance from the frizzen. If too small it may not be held securely in the jaws of the hammer. The typical hunting rifle flint is roughly ¾” by ½” (20 x 15 mm). The front edge is “beveled” compared to the back. Some locks work best with the bevel facing upward, others with the bevel facing downwards. The leading edge of the flint has to be kept sharp by “nibbling” it from time to time, taking minute flake fractures and keeping it square to the face of the frizzen.

THE BULLET

Most flintlock rifles for hunting are designed to use a round ball with a fabric patch to seal the bore and grip the rifling. The rifling twist will be 1:66” to 1:75” though some rifles have a “compromise” twist rate that’s suited to round balls or conical projectiles (usually 1:48"). Round balls are usually very accurate, and conical bullets aren’t really necessary in most hunting scenarios for medium sized game. There are some who are skeptical about the effectiveness of round balls, but they are entirely suitable for deer-sized game at ranges up to 100 yards. North America and nearly all of sub-Saharan Africa were originally colonized by Europeans armed with rifles shooting round balls. Lewis and Clark went to the Pacific and back depending on them and the “Mountain Men” who roamed the untamed American West in the early 19th Century used them. If a frontiersman in Colonial times could survive using round balls it ought to be obvious that properly understood and properly used, they will do what is needed just as well in the 21st Century as in the 18th and 19th. If your rifle shoots conical bullets well, of course there is no reason not to use them.

SIGHTS

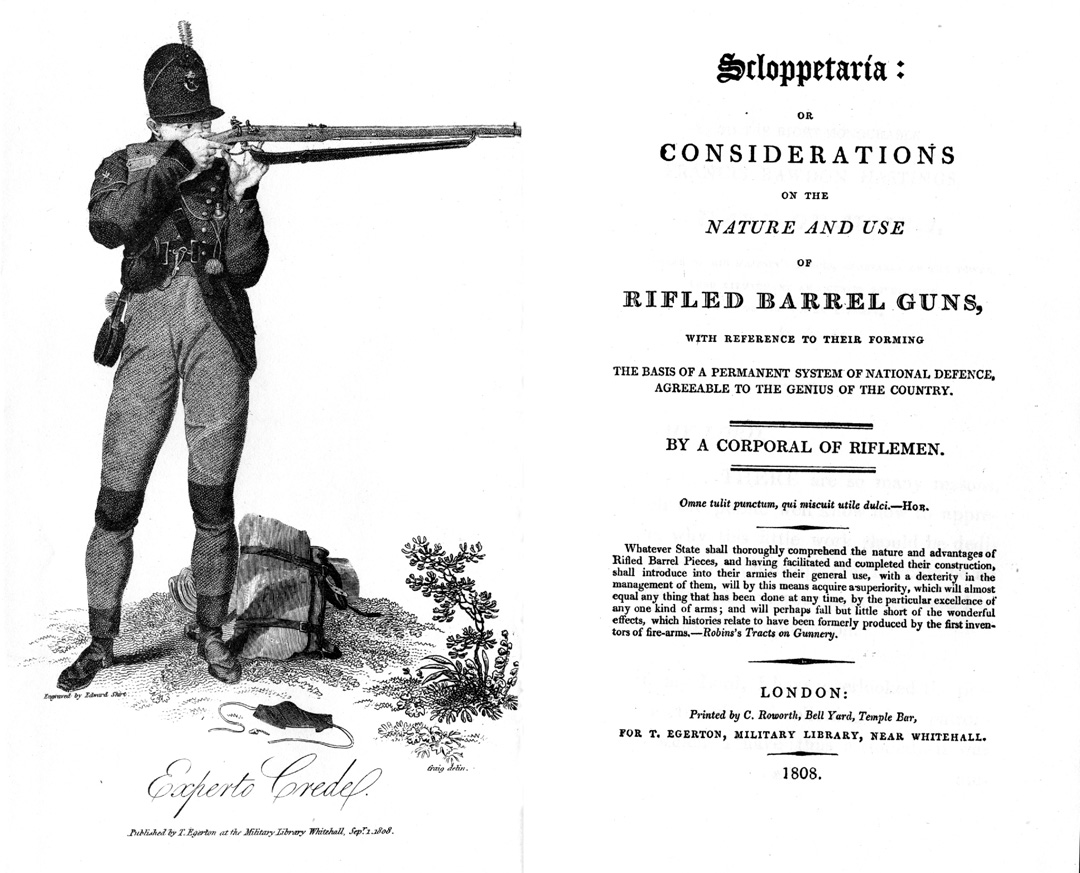

I have never seen a flintlock rifle wearing a telescopic sight. This is not to say it can’t be done: it was done, long ago. Captain Henry Beaufroy, a sharpshooter in Britain’s elite Rifle Regiment fought in the Peninsular War. In 1808 he wrote an intriguing book entitled Scloppetaria: Or, Considerations on the Nature & Use of Rifled Barrel Guns. Beaufroy has this observation on the matter of telescopic sights:

Others…have had a small telescope instead of an after-sight: the accuracy with which shooting may be conducted in this manner, is amazing; for though it required much trouble to arrange the apparatus…once done…the bullets would cut repeatedly one into the other, and not infrequently a second shot would…scarcely…leave any indentation on the edge. Their liability to be out of order, however, has precluded their frequent introduction; the sight being adjusted by means of two cross wires in the tube…the…jar of the piece in firing will very soon alter their position and consequently their accuracy can no longer be depended upon…

The frontispiece from Sir Henry Beaufroy's famous work. He used the pseudonym "A Corporal of Riflemen," though he was in fact an officer. This book is a fascinating compendium of all that was known about the science of rifle shooting at the time; and Beaufroy knew his subject, because he was a veteran of a hard-fought and vicious campaign. The Rifle Regiment was one of the most effective units in the Peninsular War; so much so that the French summarily executed anyone captured with a rifle in hand!

Today’s rifle scopes are far more rugged than those of the late 18th Century, but a scope on a flintlock remains problematic if for no other reason than that powder residue from the priming charge will coat it, and it’s difficult to clean off. Cleaning a gun using black powder is an exercise requiring hot water and soap, and not too many modern rifle scopes take kindly to that sort of treatment. Bottom line: while it may not actually be sacrilegious to put a scope on a flintlock hunting rifle, it’s not a practical proposition even 200+ years after Beaufroy pooh-poohed the idea.

However, one very practical form of rear sight that’s considerably more precise than the usual minuscule open sights found on flintlocks is a peep sight. These are sometimes available as accessories or after-market add-ons. The best kind is the sort that’s mounted on the tang of the rifle. A peep sight is instinctive in use, and especially for those of us who have reached an age when our eyesight needs a little help, it’s a much better option than open sights. If you add a peep sight to your rifle, choose one that’s rugged, simple and positive to adjust, adjustable for windage, and that will stay adjusted. Windage adjustment is more important than elevation. The latter can be dealt with by holding over or under the target if need be, but it’s very hard to compensate for a rifle that shoots off center.

The front sight should be highly visible. A large gold or white bead on the top of the sight helps, especially in low light. If your rifle hasn’t got a very visible bead, simply put a dab of white paint on it!

CALIBER

What caliber is best? That’s one of those truly un-answerable questions, but worth addressing. Pioneers in eastern North America went for fairly small bores: typical “Kentucky rifles” were .40 to .45 because lead was expensive stuff on the frontier and the smaller the bore the more balls per pound. When you have to carry every ounce of cargo on your back,  that matters a lot. A .40-caliber ball was adequate to kill whitetails (and Indians) and often it didn’t penetrate fully, allowing bullets to be recovered from game and melted down for re-moulding.

that matters a lot. A .40-caliber ball was adequate to kill whitetails (and Indians) and often it didn’t penetrate fully, allowing bullets to be recovered from game and melted down for re-moulding.

In Africa and in North America as the frontier moved westward animals were bigger, tougher, and often dangerous. The lightweight small-bore rifles of the east weren't up to the job so the average caliber used in these places was larger, anything from .50 up. Lewis and Clark used .54’s and the voortrekkers who pushed north from the Cape of Good Hope would have used similar calibers for hunting and defense.

It’s important to realize the significance of bullet diameter in black powder guns. The modern belief that velocity is the prime measure of effectiveness doesn’t apply in this context. When using round balls the only way to get better performance on game is to increase the caliber and therefore the weight of the ball. In the mid-19th Century big game hunters in Africa frequently used rifles of .75 caliber or larger on big antelope. The famous hunter F. Courtney Selous (at left) turned to a “4 bore” rifle to hunt elephant. This monster weighed close to 40 pounds and had a bore diameter somewhat larger than an inch. It fired a round ball that weighed a quarter of a pound: such a gun likely kills at both ends. If a hunter knows what he’s doing and is a calm and cool shot, I suppose that hunting the Big Five with a flintlock 4-bore would be an exciting and challenging pursuit, but most hunters have no need to go to such extremes.

The most common muzzle-loading rifle caliber by far these days is .50, which is certainly adequate for game the size of a whitetail, even a very big one. The .50 caliber components are easily found in shops or catalogs. Because the .50 is such a popular size, components in other calibers might not be so readily obtainable, but they can be purchased through catalogs.

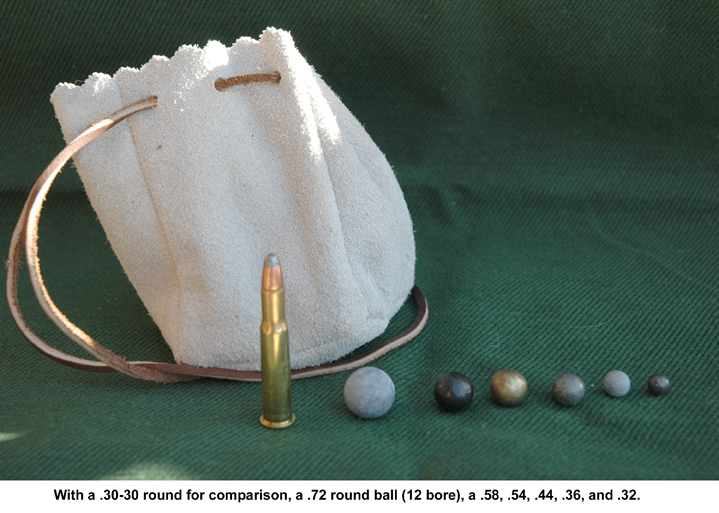

I own muzzle-loading rifles from .32 to .72 caliber, but my preference for hunting medium game is a .54. There’s nothing wrong with a .50: I’ve made several kills with one, but I want the option of using my rifle on game that runs larger than our local deer. When cast of pure lead, a .54 round ball weighs 237 grains, compared to the .50’s 188 grains; that extra weight gives the bigger ball a bit more “punch.” I own and have hunted with a .58, which was very effective, indeed: its round bullets weigh 294 grains. A .72 caliber round ball weighs a whopping 550 grains and would handle just about any animal in North America. A .50 round ball will go all the way through a deer broadside, almost every time; a .54 will always do so. How much more penetration is needed than a complete pass-through?

SHOOTING A FLINTLOCK

The fundamentals of shooting any rifle well are the same with a flintlock as any other; but any problems the shooter has with his technique will be exacerbated. In particular, if someone has a tendency to flinch, it will be a real issue when shooting a flintlock rifle.

The ignition of the priming powder produces a substantial amount of flash, noise, and smoke. More to the point, this takes place within a few inches of the shooter’s eye. It’s very distracting to have a small explosion go off right in front of one’s face! Shooters who do tend to flinch often develop a worse flinch as a result, and this causes misses. The flash and puff may send a few specks of “stuff” towards the face now and then, reinforcing the tendency to shy away. A well designed lock will incorporate a “fence,” a surrounding bit of metal behind the pan, to deflect the debris of the priming discharge. Because the priming pan is to one side, anyone standing next to it is even more subject to being peppered. In the days when flintlock muskets were used by troops standing in ranks, a detachable side fence was sometimes employed to protect the eyes of the man to the shooter’s right.

Lock Time

By comparison to fixed ammunition, and even to most percussion ignition rifles, flintlocks have a comparatively long “lock time,” the interval between ignition of the priming charge and that of the main charge. It’s often perceptible: a distinct “POP-BANG!” sort of noise with perhaps a quarter of a second between the two sounds. The reasons for it are many: a poorly designed flash channel, a flash hole that’s too small, an inadequate priming charge, a poor spark, a weak mainspring, bad lock geometry, etc. There are ways in which proper lock design can reduce lock time and over the centuries most of them have been worked out, but the fact remains that a relatively long lock time is a feature of this ignition system.

Archery hunters know that sometimes a deer will hear the “twang” of a bow before the arrow arrives, and be off in a flash: the term for this is “jumping the string.” Something similar can happen with a flintlock. If the flash of the priming and the smoke it makes are visible to the game that quarter-to-half a second before the main charge fires may be all it needs to effect an escape.

All good rifle shooters understand the importance of “follow through,” i.e., holding the sight picture until after the bullet is on its way. Long lock time increases its importance as part of accurate shooting technique. The flintlock rifleman must develop the discipline to “follow through” for longer than with a conventional rifle by a substantial amount. The clouds of smoke from both the priming and main charges obscure the shooter’s vision and don’t help. Not being able to see the results of a shot for as much as half a second after it’s on its way emphasizes the importance of follow through. Aside from flinching, failure to follow through properly is one of the principal reasons for missing.

Set Triggers

This rifle is equipped with a "set trigger." The rear lever pre-loads the internal sear, and once "set" even the lightest touch on the front trigger will fire the rifle. Set triggers do enhance accurate shooting, but they're dangerous if improperly adjusted. If set too light, even a small jar to the action will cause a discharge.

Many flintlocks have so-called “set trigger” systems. In a rifle so fitted there are two levers. One (usually at the rear) “sets” the mechanism: it pushes the sear part-way to its release point. That creates a “hair trigger” condition in which the slightest pressure on the front—the true—trigger causes the cock to fly forward and the rifle to fire. Set triggers are often used on target rifles because they do minimize the disturbance of sight picture when the shooter finally decides to fire, but they have some drawbacks in the field.

First of all, set triggers are inherently dangerous: once the mechanism is “set” the gun may discharge unexpectedly due to a bump or an inadvertent touching of the front trigger. Set triggers demand constant and scrupulous attention to muzzle control and to the rule of “Don’t put your finger on the trigger until ready to shoot.” The hunter who is preparing to fire at an animal may unconsciously touch the front trigger as he gets ready, and that will produce a miss. When moving the rifle into firing position, bumping against a branch or twig may be all that’s needed. Set triggers can be so sensitive that even breathing on one will make the gun go off, and if that’s the case it must be corrected before the gun is used at all. Any set trigger should be verified by a competent gunsmith who’s familiar with them to make sure it’s not dangerously light.

First of all, set triggers are inherently dangerous: once the mechanism is “set” the gun may discharge unexpectedly due to a bump or an inadvertent touching of the front trigger. Set triggers demand constant and scrupulous attention to muzzle control and to the rule of “Don’t put your finger on the trigger until ready to shoot.” The hunter who is preparing to fire at an animal may unconsciously touch the front trigger as he gets ready, and that will produce a miss. When moving the rifle into firing position, bumping against a branch or twig may be all that’s needed. Set triggers can be so sensitive that even breathing on one will make the gun go off, and if that’s the case it must be corrected before the gun is used at all. Any set trigger should be verified by a competent gunsmith who’s familiar with them to make sure it’s not dangerously light.

But why use a set trigger in the first place? Because the mechanism of a sidelock is such that all the operating parts are attached to the inside of the lock plate, and the trigger is merely a lever that impinges on the sear. The trigger is usually pinned to the trigger guard (or even the wood of the stock) and isn’t actually part of the lock proper. A fair amount of leverage is needed to trip the sear: the “set” mechanism does this part way, allowing the rest to be done with minimal effort. Most such trigger systems will fire when only the front trigger is used, but it takes considerably more effort and so there’s more potential for disturbing the sight picture.

Another concern with set triggers is that they make noise. Setting is accompanied by a distinct “click” which may be heard by the quarry. There’s no way to mask it. If the animal is very close or has exceptionally good hearing, it may be alerted to danger by the slightest noise, especially one of mechanical origin.

A FLINTLOCK SHOOTER’S BASIC TOOLS

Flintlock shooters need to carry a small set of dedicated tools. Bullets, patches, wads, speed loading devices, ramrod attachments, etc. are the same as those used in percussion guns and needn’t be dealt with here.

The "flint wallet" with 1) a spare flint; 2) a spare flash channel liner; 3) the tool to remove and replace the channel liner, in this case a hex key; 4) a priming flask with 4Fg powder and a dispensing spout; 5) an extra piece of leather to pad the jaws of the cock; 6) a single-edge razor blade; 7) a piece of 150-grit sandpaper to polish the frizzen; and 8) a slotted tip for the ramrod, to use in swabbing the bore

As well as the tools, the shooter will need a “flint wallet” holding a few extra flints, an extra piece of leather, some soft wiping cloth, and a couple of squares of fine sandpaper. The wallet is also handy for carrying a cleaning attachment for the ramrod, and some lubricant. If the shooter prefers not to use pre-cut patches, he will need a very sharp “patch knife” (or a razor blade) for use in loading the gun. Most will also carry a small flask for the very fine priming powder. These items are in addition to the other things any muzzle-loading hunter has to bring along: a flask of powder for the main charge, balls, patching material for the ball, and a non-sparking powder measure.

The flint wallet has pockets to hold everything except the larger tools. The wallet and any other assorted stuff (patches, wads, spare bullets, lubricant, cleaning rags, a slotted tip for the ramrod when using it to swab the barrel, etc.) go in a “possibles” bag worn on the hunter’s hip or over his shoulder. I don’t know where the name of the bag comes from, but perhaps it’s because it carries everything you could “possibly” need?

A ring carrying basic tools: a pan brush to sweep the priming pan clean; a vent pick to keep the flash channel clear; a small screwdriver to adjust the jaws of the cock; and a brass, non-sparking hammer to nibble the edge of the flint to keep it sharp

A small vent pick to keep the flash channel clear is essential. Another indispensable item is the screwdriver used to tighten the jaws on the cock when replacing or adjusting a flint. The necessity of keeping the pan clean and free of residue means a small stiff brush is part of the tool kit; and a little hammer made of non-sparking brass is used to “nibble” the leading edge of the flint to keep it sharp. Most new-production flintlocks have a replaceable flash channel liner of stainless steel, so the screwdriver can be used to unscrew and replace that. Some makes of guns have a liner that’s removed with a hex wrench, and if so, one of those should be carried. It’s a very good idea to have an extra flash channel liner if the one in place gets lost when it’s removed for any reason. In addition, a small piece of fine sandpaper (150 grit) is helpful in keeping the frizzen face polished and smooth. A couple of spare flints and a piece of leather to pad the jaws of the cock and a razor blade to trim that to size complete the necessities.

One very handy item is a specialized flask to carry the priming powder. Priming powder should be very fine grained: 4Fg is normally used, but 3Fg will work if you can't find that. You don’t need much priming powder in the pan, only perhaps 2-3 grains, just enough to fill the pan halfway. The priming flask, like the main flask, has to be of non-sparking material such as brass. The best type of flask has a spring-loaded dispensing spout. Pushing the spout against the pan deposits a small pre-measured bit of the powder into it. Experience soon shows how much (or how little) priming powder is needed. Too much priming powder may actually lengthen lock time by creating a “fuse effect.” The minimum amount of priming needed for reliable ignition is best.

SAFETY

The basic rules of firearms safety apply, always: but there’s one thing specific to a flintlock that needs to be stressed. This is the matter of “self-priming.”

Most states prohibit the transport of loaded rifles in a vehicle. To spare hunters the inconvenience of drawing a charge from the rifle, they sometimes will consider it sufficient to empty the priming charge from the pan, and thus render the rifle “unloaded.” Nine hundred and ninety-nine times out of a thousand that’s the case, but not always. Because the flash channel is open to the pan a bit of the main charge powder can leak out of it and find its way into an otherwise-empty priming pan. It need only be a few granules to create a very real hazard; snapping the lock may ignite those stray granules, and set off the main charge. When examining or handling a flintlock rifle, it’s essential to be absolutely, positively certain that there is no main charge in it. Snapping the lock to test the degree of sparking is a dangerous practice when there’s a charge in the gun.

One simple and effective safety device that can obviate an unintended discharge is a “frizzen stall,” shown above. This is simply a leather sleeve that covers the frizzen face. If somehow the lock is tripped it will prevent any sparks from being generated.

THE HUNT

You’ve made the decision that your next hunt will be with a flintlock, determined the proper load from the manufacturer’s manual, and have sighted the rifle in. Then you’re ready to hunt. Keep in mind the things discussed here as you do.

The long lock time make shots at running animals problematic. It’s hard to determine “lead” when you don’t know for sure how long it will take the gun to go off. Stick with standing animals and take broadside shots. A flinch induced by the flash of the priming will usually result in a miss, with the shot going low. You have only one shot, so make it count. Reloading the rifle takes a couple of minutes even with practice, and you can’t do it while running. Better to pass up the shot than to wound and be unable to follow up quickly.

Be prepared for a misfire or a hangfire. These are part and parcel of the flintlock ignition system, and sooner or later it will happen to you. As frustrating as such an event may be, it’s one of the realities a flintlock hunter has to accept.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND SOURCES OF SUPPLY

An indispensable source of information and muzzle-loading lore is the publication Muzzle Blasts, published by the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association in Friendship, Indiana. NMLRA is dedicated to the sport of muzzle-loading in general and their monthly magazine covers “how-to” pieces, collector’s lore, articles about hunting, historical information about the early frontier period, battles in which flintlock rifles played a significant part, and much more. Many custom gun builders and “sutlers” advertise in it as well.

High quality mass production flintlock rifles are sold through commercial outlets including the well-known catalog retailers (e.g., Cabela's, Midway USA, and Dixie Gun Works) and sometimes can be found on the racks of larger sporting goods stores. Some very well-known names in the gun business make flintlocks including Traditions, Davide Pedersoli, and Euroarms. All these makers have web sites. Used guns are also worth considering. Alas, Thompson-Center, who used to make some of sturdiest and most reliable production flintlocks has ceased production of sidelock guns, but they can often be found used on auction sites and in shops. If you’re flush with money, you can order a custom-made rifle from any number of builders who will tailor a rifle to your specifications and present you with a work of which any 18th Century gunsmith would be proud. Many such custom builders and parts suppliers advertise in Muzzle Blasts.

In addition some retail outlets specialize in muzzle-loading guns, including flintlocks. These include (but aren’t limited to) Track of the Wolf, October Country, The Gun Works Emporium, and the Log Cabin Shop. All of these places have web sites for ordering. You can order parts from these places if you have the “itch” to make your own rifle. Eighteenth-Century gun makers bought the locks and barrels as pre-finished parts and assembled the guns bearing their names on stocks they made: you can do the same. Needless to say the vendors also can supply balls, patches, flints, and other necessities.

So if you’re beginning to feel that hunting with a conventional rifle is a bit “too easy,” and would like a real challenge, you’re ready to hunt…with a flintlock. Get out there and give it a try!

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |